I don't think that I fully understood Vincent van Gogh's paintings until I stood in an olive grove in St-Rémy de Provence, France. I'd seen plenty of his paintings before--too many reproductions to count and even a few real ones--and I liked them in a general sort of "doesn't everyone?" kind of way; the colors are vibrant, the brush strokes convey a kind of urgency and there's an intensity that's hard to ignore. This particular olive grove sits outside the walls of St. Paul de Mausole, a 12th-century Augustine monastery that became a psychiatric hospital in the 1800s. On Backroads' Provence Walking & Hiking trip, we met up among the trees with Marie-Charlotte Bouton, an art historian with a passion for van Gogh. Marie-Charlotte is petite, lively, always beautifully dressed and has blue eyes that sparkle when she talks.

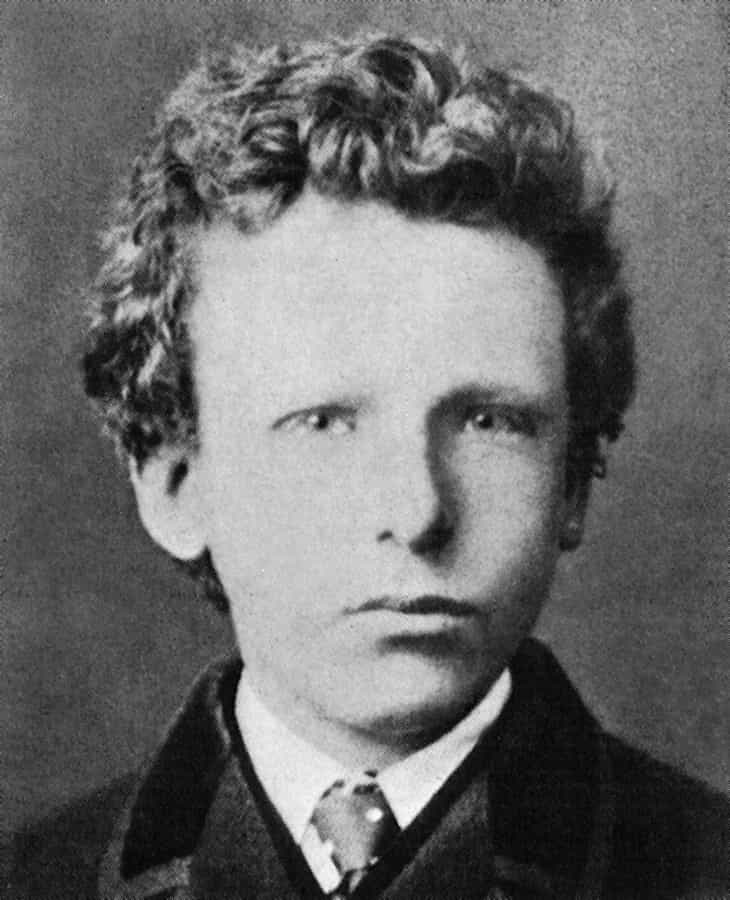

She began by telling us about van Gogh's early years and showed us photographs of him as a child. Somehow these surprised me--his life seems sufficiently long ago that it doesn't coincide with whenever I imagine the camera was invented. But there he is looking young and serious. While he drew and was artistic as a child, he studied religion as a young man and aspired to be a minister like his father. It wasn't until he was 27 that he began to paint and study to be an artist. He enrolled in the Royal Academy of Art in Brussels and later graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium.

We know him for his loose style and bright colors, but his first paintings were much more traditional. Detailed and dark, they look more like the Dutch masters from his native country than anything influenced by the French Impressionists. Still standing between the olive trees, Marie-Charlotte showed us how his paintings transformed as he moved south into France, first to Paris in 1886 and then to Provence in 1888. It was here that his work became that of the van Gogh we know: filled with sunlight, intense yellows contrasting with deep blues, portraits, night scenes, still lifes, flowers, paint thick enough you can see the brush strokes... Despite the beauty of his canvases, van Gogh's life was not easy. We've all heard about the ear-cutting incident in Arles, but sadly that wasn't an isolated fit of artistic madness. Instead, he suffered profoundly for the majority of his life with what is thought to have been bipolar disorder along with epilepsy and periods of deep psychosis. Realizing the depths of his own suffering, he checked himself in to St. Paul de Mausole in May, 1889.

The hospital became a sanctuary, and the structure and limits helped stabilize him somewhat. He stayed for one year and those 52 weeks were some of his most prolific. He completed 143 oil paintings and over 100 drawings during his stay, including some of his best-known: irises, olive orchards, wheat fields and one beautiful Starry Night. As Marie-Charlotte wove the stories of his life with his paintings, it was easy to imagine him venturing out from the monastery walls to set up his easel in the olive grove. His self-portraits from this era show a thin and haggard man with haunted eyes, but his paintings of the olive trees and surrounding Alpilles mountains contain a clarity at odds with what must have been a dark and confused internal world. We stood a little while longer, shifting our gaze between a print of Olive Trees in a Mountainous Landscape and the actual mountains, taking in van Gogh's version and comparing it to the real thing. Just then, the breeze picked up and the famous Mistral wind blew through the trees, shifting the leaves from green to sliver to green again.

It was the wind that somehow brought it all together in my mind: the painter with the internal tempests, the external gusts that probably made him hold on to his canvas so it didn't blow away and all that movement that he captured so perfectly in paint. I wondered, "Was the weather just like this the day he stood in the olive grove? Clear, crisp and sunny with a stiff breeze?" Suddenly it dawned on me that he was not only trying to show us what the place looked like, but also what it felt like. Nothing in his canvases from St-Rémy are really still--the clouds swirl, the stars spin and the leaves on the trees are tossed back and forth--and to me it will always seem like he was trying to paint the wind.